Exploring Diagnosis-Related Allegations in Otolaryngology Claims: The Complexities of Clinical Reasoning

Laura M. Cascella, MA, CPHRM

Diagnostic errors are a persistent issue in healthcare, and they are a top liability risk for many medical specialties. A review of 10 years of malpractice claims data for otolaryngology shows that diagnosis-related allegations account for slightly more than a quarter of claims.1

Although the volume of diagnosis-related claims is significantly lower than the volume of claims for the top allegation category in otolaryngology — surgical treatment and procedures — these cases still can be consequential in terms of poor patient outcomes and total dollars paid (i.e., expense and indemnity dollars).

Diagnosis-related otolaryngology claims often involve oropharyngeal cancers, and many allegations are related to breakdowns in the diagnostic process, such as:

- Inadequate assessment and evaluation of patients’ symptoms

- A narrow diagnostic focus and failure to establish differential diagnoses

- Delays or failures in ordering appropriate diagnostic tests

A common contributing factor in diagnosis-related claims for all specialties is clinical judgment, which includes clinical reasoning and decision-making. In otolaryngology, clinical judgment is noted as a risk factor in almost every diagnosis-related allegation.

Because clinical judgment is a complex process that involves various cognitive functions, it’s easy to understand why it is a driving force in diagnosis-related claims. Much of the literature focusing on diagnostic errors and clinical reasoning recognizes the dual decision-making model, which consists of two reasoning systems as the basis for clinicians’ diagnostic process.

In System 1, the reasoning process is automatic, intuitive, reflexive, and nonanalytic. The clinician arranges patient data into a pattern and arrives at a working diagnosis based on past experience, knowledge, and/or intuition. In System 2, the reasoning process is analytic, slow, reflective, and deliberate. This type of thinking often is associated with cases that are complex or novel, and System 2 thinking involves more cognitive workload and resources.2

System 1 and System 2 are not mutually exclusive, and clinicians tend to use both, depending on the circumstances. Although research suggests that most clinical work involves System 1 reasoning — particularly as clinicians gain more experience and knowledge — both systems of reasoning are vulnerable to cognitive errors.3

Research about the cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors suggests that errors in clinical reasoning often arise from several sources, including faulty heuristics, affective biases/influences, and situativity.4

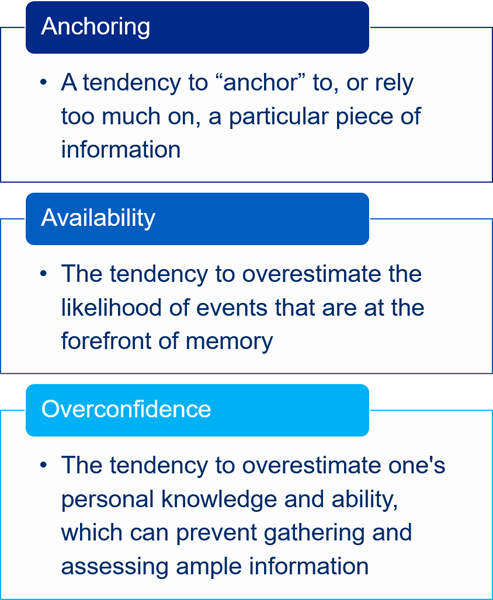

The term “heuristics” refers to mental shortcuts in the thought process that help conserve time and effort. These shortcuts are an essential part of thinking, but they are also prone to error. Cognitive biases occur when heuristics lead to faulty decision-making. Some common biases included anchoring, availability, and overconfidence.

The term “affective influences” refers to emotions and feelings that can sway clinical reasoning and decision-making.5 For example, preconceived notions and stereotypes about a patient might influence how a practitioner views the patient’s complaints and symptoms.

“Situativity” is an umbrella term used to describe a series of cognitive theories that examine clinical judgment and reasoning in the context of the situations in which they occur. These theories look at how the dynamics of various situations, such as people and technology, may affect cognition.6

Although cognitive processes are well-studied, further research is needed to determine how best to prevent the flaws in clinical judgment that can lead to diagnostic errors. A number of potential solutions have been proposed, including implementing strategies to improve teamwork, adjusting processes and workflows, using diagnostic aids, and exploring debiasing techniques. Yet, researchers note that “unless [these strategies] are well integrated in the workflow, they tend to be underused.”7

| Examples of Diagnostic Aids |

|---|

|

Thus, carefully considering how to implement various diagnostic strategies in everyday clinical activities may help otolaryngologists begin to take steps toward managing diagnostic risks. A helpful resource is the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine’s Clinical Reasoning Toolkit for trainees, clinicians, and educators. The toolkit supports awareness and better understanding of diagnostic reasoning, cognitive psychology, and diagnostic errors. Resources within the toolkit include links to books and articles, slide presentations, and videos focusing on clinical reasoning and cognitive errors.

Endnotes

1 MedPro Group. (2023). Otolaryngology & otorhinolaryngology (ENT): Claims data snapshot. Retrieved from www.medpro.com/documents/10502/5086243/Otolaryngology.pdf

2 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2015). Improving diagnosis in health care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; Nendaz, M., & Perrier, A. (2012, October). Diagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning: Mechanisms and prevention in practice. Swiss Medical Weekly, 142, w13706; Phua, D. H., & Tan, N. C. (2013). Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 42(1), 33–41; Ely, J. W., Graber, M. L., & Crosskerry, P. (2011, March). Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors. Academic Medicine, 86(3), 307–313.

3 Phua, et al., Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors; Nendaz, et al., Diagnostic errors and flaws in clinical reasoning; Crosskerry, P., Singhal, G., & Mamede, S. (2013, October). Cognitive debiasing 1: Origins of bias and theory of debiasing. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(Suppl 2), ii58–ii64.

4 Phua, et al. Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors.

5 National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Improving diagnosis in health care; Crosskerry, P., Abbass, A. A., & Wu, A. W. (2008, October). How doctors feel: Affective influences in patient’s safety. Lancet, 372, 1205–1206; Phua, et al. Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors.

6 Merkebu, J., Battistone, M., McMains, K., McOwen, K., Witkop, C., Konopasky, A., Torre, D., . . . Durning, S. J. (2020). Situativity: a family of social cognitive theories for understanding clinical reasoning and diagnostic error. Diagnosis, 7(3), 169–176. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0100

7 Ely, et al., Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors.